- Platform

Platform

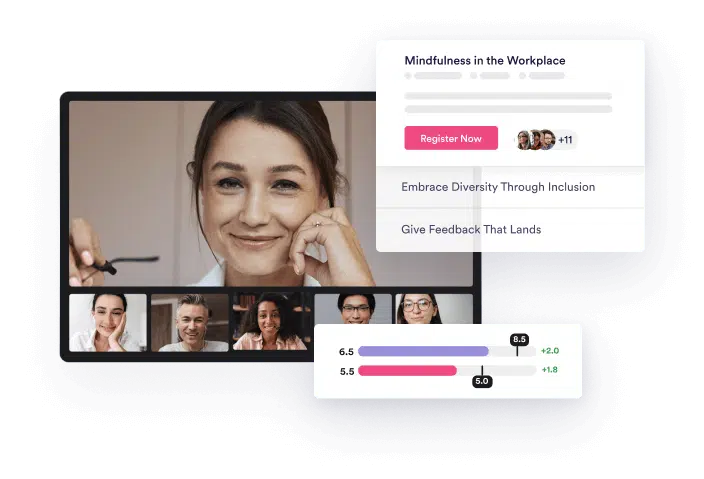

Easily manage and scale your L&D initiatives and reinforce learning beyond the classroom.

- Why Hone?

When Self-Paced eLearning Isn’t Enough

After teaching hundreds of thousands of learners, we’re sharing the secrets behind our world-class training methodology that produces real outcomes.

- Resources

Keeping employees engaged and motivated can feel like an uphill battle. With companies experiencing everything from a volatile economy, budget changes, and layoffs to the rise of remote/hybrid work, navigating AI, and more — change has been the only constant. This webinar will give you the tools and strategies you need to keep your employees inspired and productive, no matter what comes your way.

65 min

What's covered

Tom Griffiths is joined by Mike Rognlien, a learning executive and author, who was a founding member of Facebook’s L&D team and helped the company scale from 1,500-26,000 employees.

In part 1 of our conversation, Mike shared his learnings on building culture in a high-growth environment. Make sure to check that out to hear even more from Mike.

In part 2, we’re going to do a deep dive into how you can build effective L&D programs to enhance performance and build a culture at the same time, as well as how you can align training to solve real business problems,

About the speakers

Mike Rognlien

Sr. Director of People Development at Lacework

For over 20 years, Mike has learned from and taught some of the best (and some of the.. not best) people in the corporate world. He’s taught everything from how to present to how to manage global teams, and a whole lot in between in organizations as small as five people and as large as 100,000 or more.

Before starting his own company, Mike was one of the founding members of the Learning & Development team at Facebook, where he spent almost 7 years building all things learning — onboarding, manager development, hard conversations, and, in partnership with COO Sheryl Sandberg, the company's Managing Unconscious Bias training.

His tenure at Facebook, as a consultant to Microsoft, and at numerous other companies — from insurance to banking to Silicon Valley — taught him valuable lessons in responsibility, ownership and accountability, and the never-ending but rewarding work of building thriving and honest workplace cultures. His extended team, located around the US and in Europe, Asia-Pacific and Latin America, is a sought-after group of expert facilitators and coaches with decades of experiencing building great people and teams.

She is the author of Virtual Training Tools and Templates: An Action Guide to Live Online Learning (2017), The Virtual Training Guidebook: How to Design, Deliver, and Implement Live Online Learning (2014) and Virtual Training Basics, 2nd edition (2018).

Tom Griffiths

CEO and Co-founder, Hone

Tom is the co-founder and CEO of Hone, a next-generation live learning platform for management and people-skills. Prior to Hone, Tom was co-founder and Chief Product Officer of gaming unicorn FanDuel, where over a decade he helped create a multi-award winning product and a thriving distributed team. He has had lifelong passions for education, technology, and business and is grateful for the opportunity to combine all three at Hone. Tom lives in San Diego with his wife and two young children.

Tom regularly speaks and writes about leadership development, management training, and the future of work.

Episode transcript

Tom Griffiths

Alright, we're back with Mike Ronglien. I'm super excited to continue our conversation. In part one, we went deep into the culture and his time at Facebook and how that evolved. In part two we're gonna talk about the role of l and d in shaping that culture and helping the company succeed. Mike, you were head of L and D at Facebook for over seven years.

What role do you see for L and D in building or maintaining that company culture?

Mike Rognlien

Yeah, so I think first and foremost is what we were talking about in the first segment, the difference between being a training department and a learning and development department. Stu, who we're talking about on break, is the guy that hired me on Facebook.

That was one of the things I think that philosophically, we were very aligned on was that I had no desire to come in and just build a training repository of a hundred different classes. I really wanted to, and they gave me as much as you could take a lot of time. They gave me some time in the beginning to really get a sense of.

What is the special sauce that makes this company work? And what are the skills that are behind those things? So we talked about being open and moving fast, no matter how much you can nod your head and say, yeah, that sounds awesome. Living up to it is a whole nother ballgame.

So I think the most important thing that any L and D team can do is to really say, what are those critical skills that we absolutely will not have in this culture? We will not be able to live up to these values unless we teach people them. And just relentlessly, Cheryl called it ruthless prioritization but really making painful decisions to say, I would love to be able to do five things next year, but we're gonna choose these three because they're the most culturally relevant.

And it's funny 'cause this has been such a walk down memory lane 12 years ago when I started; I remember one of the first meetings that we had as an L and D team after I started was to really decide what are we gonna focus on? What are we gonna prioritize? And one of the things that people had been asking about was some kind of interpersonal communication skills type program. We were very engineering-heavy heavy, very young. All of our managers, including, I think, Mark was 26 or 27 when I started. So there was a lot of really incredible talent, but from a soft skills perspective, it wasn't necessarily as advanced. We said we would really love to do some kind of interpersonal skills training, but it's just not as important as onboarding and a co and some other manager development stuff.

So we deprioritized it and then, I don't know, it was May, I think it was maybe the end of my first or second month with the company, and Cheryl did an internal talk for managers and leaders. And she did her, here are my thoughts on managing and leading and what I'd like to see you all do here at Facebook.

And at the end, somebody got up and asked, "What's your biggest concern about the company as we're about to, do this, go through this vertical growth ramp, not just in terms of the product, but in terms of the people?" And she didn't miss a beat. We're gonna stop being open and honest with each other.

People are gonna know each other less, so they're gonna be less direct and all of the kind of negative side effects that come with less direct communication are gonna befall us. And Lori, who ran the people team, was sitting on one side of me and Stu, my boss was sitting on the other side and we had just recently decided we weren't gonna do any type of interpersonal communication training.

And I just looked at both of 'em like, are we really not gonna do this? Like she's both, she's all three of our boss. Are we really not gonna do the thing that, addresses her biggest concern and they were like, Nope, let's go back to the drawing board. And in the spirit of moving fast and being bold and all of those value-based decisions, we reprioritized and added in a class called Crucial Conversations which I had taught at Microsoft and was a big advocate for.

And six weeks later we launched that program globally. And. I don't know if they still, I believe they still offer it, but in my time it became not only the most popular program in the company but also the most culturally reinforcing. It just, came up all the time and became a lot of the skills underneath that program, having them be present and having them be so prioritized and talked about and discussed in the culture.

Made it, I think, a lot easier for us to launch the unconscious bias training that we ended up building a few years later. And that's, I think, by the way, why Cheryl wanted me to help her build it was because I had operationalized that crucial conversation implementation really quickly. And it was, they became two topics that we really bonded over.

Tom Griffiths

Wow, there's so much in that and what you just said. First and foremost, wanna give Stu a shout out. As you mentioned him there, he was an advisor at Hone in our early days, and helped us build a lot of early content, so thank you Stu. And yeah, just sounds like you, as a learning team, lean and mean really embracing that move-fast culture in how you were.

Supporting the organization and talking a lot to learning leaders and people, leaders about how you can get a seat at the table or work more strategically with business leaders, and listening deeply to concerns that Cheryl had. And then building learning programs directly to address those. Seems, you know exactly the right kind of way to build that relationship and support the strategy more effectively. So that's great. It sounded like you three four or others built a lot internally or adapted stuff internally. And just curious how you brought the values into the content. 'cause I know you wanted to tackle the subjects head-on but did you bring in the kind of mantras we were talking about earlier, how did you actually make it feel like Facebook when you built the training?

Mike Rognlien

I love that you asked that question. 'cause professionally and from a personal perspective, speaking professionally, I think my proudest contribution, not just to learning and development at Facebook, but really to the profession was. the ways that I went about and that we went about building customized versions of content with these vendors.

There were two things that I wanted to achieve at the same time. Number one, I didn't want to build a bunch of stuff from scratch. Crucial was one of the programs. We also did situational leadership from the Ken Blanchard companies. We used a lot of Marcus's content on strengths and strengths-based leadership from T N B C.

I had no desire to reinvent any of their work. They were the best in the world. But at the same time, I also knew from teaching Crucial for years at Microsoft that I was constantly at the beginning. It became a funny thing, but also a necessary evil. I would ask at the beginning of every session of Crucial, raise your hand if you've ever seen a really great, compelling, realistic training video.

And of course, nobody would ever raise their hands. Good. You're not gonna see any today either, and it's a lighthearted way to acknowledge the fact that the video content was really not realistic. And at Microsoft that, got the laugh and made the point and then I showed the videos anyway.

By the time I got to Facebook, I was like, these guys are just gonna eviscerate it. Yeah. They're gonna look at a bunch of mostly white, middle-aged dudes in mahogany conference rooms talking down from the 1990s talking down to younger female employees and just be like, are you kidding me with this?

I went to VitalSmarts and was like, I love, which is now crucial learning. I went to them and said, I love you guys. I love your content. It is life-changing and the way that it is presented is absolutely going to render it ineffective here. So you're gonna have to either be willing to let me and my team customize it and trust that we are enamored enough with and in love with your content and the research behind it to do it justice, or we're gonna have to figure out something else. And to their credit, they were like, all right, we've never done a deal like that before. We've always just said, okay, here's the number of workbooks, and if you need trainers, here's how much that costs.

And then, go implement. And we did, we completely customized it and we ended up doing the same thing with situational leadership too. And with Marcus's content, I think my biggest superpower was always being able to see how all of that stuff worked together. So our management training, which became, it wasn't just manager training, it was management training.

It was open to everybody became if every manager and leader and person in the company understands the importance of strengths and how to identify them, if they understand the way that you need to shift your approach, Allah situational leadership, as people are growing and changing, and if you're comfortable having those difficult conversations about things that pop up along the way, we really feel like you're gonna be 90% of the way there.

And so that kind of became how we built those early. Those early programs and then later programs all followed the same thing. But I built nothing from scratch. I sorted the content that I thought was the best that other people agreed was the best. And then we customized it and now, there are tons of different ways that a class like Crucial, you can customize, you can reorder slides, you can add stuff in.

You can take it out. You can do a one-day version, you can do a two-day version. There are people wearing jeans and the building isn't on fire. There are so many different things that I know because they've given us feedback that we really had a positive influence on. And I'm proud of that.

The industry was very locked down and very do it our way. We're the experts and I think it's a much more open flexible, way of getting learning out to people now. If your end goal is optimizing towards relevance and applicability at an organization you've gotta be able to tailor it to what.

Tom Griffiths

The learning leaders know what their audience is looking for and as you say, starting from scratch is also inefficient and not necessarily gonna produce the right results. So, finding that vendor partnership that you can tailor in the right way is the sweet spot.

You had a big bootcamp program at Facebook, would you have those training programs as part of that, or was it, come whenever you're ready or at certain inflection points in a career journey, how did you actually roll that out or invite people to take part?

Mike Rognlien

D, all of the above. So again, picking programs and the skills that those programs brought that were deeply cultural, culturally relevant. Because they were so culturally relevant, there were a million different ways to implement them. So bootcamp is a great example. Bootcamp was, for the unfamiliar, basically the way that we brought engineers into the company.

For years, I don't think they do this anymore, but for years the way that we hired engineers was we just hired engineering talent and then they would spend their first six to eight weeks at the company or so in bootcamp. They would just be solving problems and learning about different parts of the site, as the company and the product got bigger, there was more to experiment with, and then they would pick the part of the product that they wanted to work on.

So some people were like, I wanna work on facebook.com. Some people were like, I want to build for mobile. Some people were like, oh, Instagram's brand new. I wanna go play over there. And then there were people that were like, I wanna be behind the scenes. I wanna figure out how to make all of the servers that have to work together around the world to serve these apps on a billion, 2 billion, or 3 billion phones that's my jam. So that's where the interns that would take the site down would go, is that right?

I remember there was a like handmade banner that a woman named Melissa Han, one of the early recruiters, and her brother Bob was one of the early engineers. And I remember walking in, I think it was for my interview, and there was like a handmade, like a homecoming football game type poster.

And that said, this site is, and then there was like a space to either put up or down. And then after, it was like, good job. Anyway, so bootcamp was a way to let people experiment. So if you're gonna do that successfully, then the bootcamp mentor the people that were already there that were mentoring these new engineers, they had to be able to use the principles of like situational leadership in order to really help.

These people that are, they have six weeks to figure out basically what they want the first part of their career at Facebook to be. And so those bootcamp mentors ended up saying, that situational leadership thing that you're doing for, mainly for managers. I'm not a manager, but I am mentoring people, so I need to help.

People move through that development curve. So I need to take situational leadership. So we put that in the bootcamp training we had a number of people who were customer-facing that were like, we're pretty good internally with how we communicate, and we don't really have a lot of unhealth.

We have conflict, but it's not unhealthy. But God, some of our customers, holy crap. So it's great. Then let's come in and do a session on crucial conversations that is specifically focused on having crucial conversations with advertisers. So every skill that we picked for years, there were like five, and they were all deeply culturally relevant because they just permeated everything that we did and how we got our work done.

And that really didn't change the whole time I was there. We were doing the same kind of core courses. We added classes like bias and stuff along the way. But for the most part, we were doing the same exact programming when I left at 26,000 people that we had started with in my first six months.

Tom Griffiths

Yeah, that's such a testament to how you all set it up and fascinating that you would adapt it, like you said, for conversations with advertisers as a special case to really apply the material to that and teach people how to do it. So specifically that, that's really cool. This term learning culture bringing together, our two threads gets bounded around a lot.

I'd just be curious if you find that a useful term and how you define a learning culture and it would be great to talk about how do you build a learning culture and know that you have one?

Mike Rognlien

Yeah. Again, timely because this is a question a variation on a question that we're asking internally at Lacework.

How do we know if we have a high-performing culture? First and foremost, if you're on high high-performing culture, you have to set high goals, right? You have to have really high standards for what you're going to accomplish. 'cause if you don't have that, you can't really be a high-performing culture 'cause you're not working on stuff.

That's hard enough. I think for a learning culture. I think it's a wonderful term and it's a wonderful environment to work in, but there's a precursor to that, which is that you have to prioritize and value curiosity. You can't hire a bunch of people who are like, I already know everything I need to know, or, I've got 20 years of experience, you're not gonna teach me anything.

'cause you can't have a learning culture without learners. And learners tend to be curious. It's actually one of the things I think I got introduced to you all. Via a podcast that I had posted on LinkedIn that Jay, our CEO had done. And I was going back and forth with one of your colleagues that I used to work with at Facebook and about this podcast.

And that podcast that I had posted about was Jay talking about all of the lessons that he's learned along the way as a leader. And one of them was that he just deeply values curiosity. And he also demonstrated that Mark was the most curious executive I've ever worked with in my life, just insatiably curious about everything.

One year, he did a book club for a year where anybody in the company could, if they wanted to read the book that Mark was reading, and every other week or so, he would host a book club in his conference room which was when Facebook was probably 15 plus thousand people. So we weren't just a tiny little company.

Like it was a thing, and people would, I guess, it wasn't Zoom at the time, but they would video conference in from all over the place, and we would sit in a circle have a discussion about what, and it wasn't like, we're gonna read Oprah's book Club, nothing against Oprah's Book Club as I'm looking at Oprah's book, club book that's sitting right there.

But the one that I, the one that I went to, 'cause I was, swimming way upstream from my standard skillset was like on the ethics of mapping the human genome. It was one of the days that I think I felt the best about working at Facebook because you've got all of these people from different functions, mostly technical folks, but people from all around the company, a bunch of people on video conferencing was sitting in Mark's conference room, and his ability to synthesize and then have questions about the content in that book, which was way over my head.

I just thought what an incredible organization to work in, where the CEO of the company is taking an hour and a half out of his day on top of the time that he took to actually read and understand the book to talk and wax philosophical and poetic about the ethics of mapping the human genome with a bunch of his employees.

You can't have a learning culture without curiosity, and you really, it's, you're really hard-pressed to have a learning culture without curious leaders. I know I talk a lot about shared ownership and how everybody has skin in the game, but leaders do disproportionately influence that. And if you don't have curious leaders and if you don't have leaders who, as I said at the beginning of our conversation, leaders like Jay, who it's just baked in that they value learning.

It's really hard to do that. So I tell people that are in this profession when they're interviewing for companies, ask them, what was the last book you read? Or what was the last concept that really changed how you viewed a significant part of running your business?

Because it's gonna be pushing a boulder up a mountain to try and get them to value that type of curiosity and that dedication to continuous learning.

Tom Griffiths

It encapsulates so much that concept of curiosity and the story of Mark doing the book club for 90 minutes every couple of weeks, and making time for that is so iconic, right?

Because we hear sometimes from people, I haven't got time to do learning. I've got too much to do. We're talking about Mark Zuckerberg running Facebook and all the other acquisitions. finding an hour and a half every two weeks to just do not even work relevant learning necessarily. But just following his curiosity, and that's just such, setting such a great example for the team at Facebook, but also, I think more broadly how leaders need to make the time to prioritize learning because it models it for everybody else. And if you can do that, then it'll cascade and build that learning culture. It's an awesome anecdote. Thanks for sharing it. Are there other things that you, as a learning leader, can do? Say there's buy-in from the executive team, or maybe you need to get a little bit of buy-in from the executive team, but how do you actually operationalize a learning culture?

Mike Rognlien

Yeah, that's a really good question. So when I came into Lacework the first few meetings that I had with senior folks were really educating them about how I get my work done.

I think if you want a learning culture, again, you have to have curiosity, but you also have to understand that, especially if you're coming from nothing, which Lacework really doesn't at this point have management and leadership training. They were doing some coaching with an external vendor, and they had some programs in place, but nothing programmatic that was like, this is how we think about manager development, for example.

And it's probably a combination of, I was very fortunate at Facebook. I really didn't have to justify anything monetarily, budget-wise, philosophically, as I established early on that I'm here to focus on the most important stuff and, with people like Stu and Cheryl and Mark behind it.

It was pretty easy to just get that stuff done now, and it's a function of spending six years in consulting between my last full-time job and my current one. I am much more I spend a lot more time educating people about the process, about how this stuff has to work. So, I tend to talk about learning and development as a systemic solution.

That is dependent upon two other things in order to really work. The first is, and I'll use manager development a, and as an example. We didn't have clearly defined, communicated expectations for managers, which is not surprising. A lot of smaller companies don't even, and some larger companies don't.

And in the past, I would've been tempted to say that it doesn't matter. We're just gonna plow forward and do some training. What I know from a, from an experiential perspective, the managers that are actually being asked to take the training, Justifiably, you're like, I don't know why I would do that.

Like, why would I go to training when I have no idea how it relates to anything that's related to my job? So the first prong, I think that if you want to have that learning culture, you have to get very anchored into what are the expectations that any learning or development opportunity. Would it actually tie to why would somebody want to develop this skill?

As I said, with crucial conversations at Facebook, it was clear be open is valuable. Being able to communicate effectively and be able to handle conflict and all of that was something that you would be held to account to. So because that expectation existed culturally and professionally, It was something that people did.

The same thing applies here. So, the very first thing that I did as an L and D professional was not to roll out training, it was to roll out manager expectations. So that there's a foundation upon which to build. The second piece, which is what people in L and D are most typically known for, is the actual learning experience, which I'm working on now.

And I can't, the, a lot of these folks have not had this type of training before. They've never had it at Lacework, so I can't just go guns blazing and throw 10 different programs at them. I went around and talked to managers, leaders, individual contributors all over the company. It was like, what do you think is the most important skill for us, all of us, to get better at first?

And it was being able to give and receive feedback. Great, we'll start there. And then the third piece of it that, that, and all of this happens to some degree concurrently. The third piece is, are we gonna hold people accountable? 'cause without accountability, the expectations aren't taken, be taken seriously, and then neither will the training be.

So the third piece is how are we gonna hold people accountable? And are we going to specifically hold people accountable for their ability to meet the expectation of being good at delivering and receiving feedback? So I won't even sit down to talk about a training program until I know that we're gonna sit down and talk about all three of those things.

That in and of itself is a learning process. 'cause a lot of times, again, if you're coming from a more traditional, maybe older school training department, it's the executive asks for something, and you say, what time? Versus saying, hold on, what is the expectation? How are we gonna hold people accountable?

And when I say hold people accountable, I mean reward them for doing it really well and have there be some kind of a meaningful consequence for not doing it really well until we have that whole system mapped out. I'm not really ready to launch into a training program. I don't think that any of us are doing any of our internal or external clients a service.

If we don't, again, from a curiosity perspective, say, great that you wanna do this type of training, what expectation is it gonna map to, and what accountability measures are gonna be in place to make sure that the people that do this training are actually living up to the expectation that we've set.

Tom Griffiths

It is so powerful to link it to almost the business problem that you're trying to solve. So everybody sees that it's important, not just training for its own sake. Like you say, on the whim of an executive that may be here today, gone tomorrow. And that allows you to. Not only motivates the learners but also justifies the program in the first place and ultimately measures the success at the end.

We have a lot of conversations with our clients and folks in the industry around this question of how do I justify learning budget, especially these days when times are a little tighter. So I'd just be curious if you had any advice for people who are going through that process of trying to justify a learning program to the executive team.

Mike Rognlien

I think being, first and foremost, being willing to be as nimble as the rest of the company, right? Like when times are tight, everything gets tighter, travel. Discretionary travel gets tighter. Team development offsite stuff like that tends to get tighter. So I think first and foremost, that's one of the reasons this was all born out of necessity.

Slower times at previous companies, when I knew that things were gonna get cut, it's why don't we just not have a bunch of fat in our budget in the first place? Why don't we not? Do a bunch of training programs that aren't really needed, that aren't the most important in the first place.

Because if I can't believe I'm gonna quote RuPaul's Drag Race, but one of the things I love, RuPaul says, right? One of the things, again, is the learning culture; you can find tidbits everywhere. I love RuPaul for a number of reasons, but I. She's H"ey, if you stay ready, you don't gotta get ready."

And I think the same thing applies here, right? If, if you have the right focus, the right content, and the right prioritization, and that program, those critical few important programs that you do are deeply tied to expectations that are deeply tied to accountability. I think by taking that systemic view of learning, I think you're predisposed to being ready for it.

Spoon times and leaner times, but I've never looked at, 'cause again I, the one thing that I will tell people that was just earth-shatteringly different about Facebook was I literally had no budget. And when I say no budget, no budget limit. Like whatever we needed must be nice. It was, and I wasn't stupid about it.

I'm like, yeah, I don't need that money. Yeah. Or I know that we could do that program, but it's just gonna be a distraction. It's gonna take, again, it'll be motion but not progress. There was a lot of stuff that we didn't do, even though we would've never had to ask twice for the money for it, because it just wasn't the most important thing to do.

I was never asked to really anything in or or cut anything while I was at Facebook. I know that they have every department that the company has. But I think starting my tech career at Intel when I. They were coming off of five, I think, three stock splits in five years.

The money was flying everywhere. Everybody was spending tons of money on everything, and then the floor fell out, and the whole time I was there, it was just shrinking and cutting and shrinking and cutting, and it was painful. But it's, it's like grandparents that grew up during the depression.

They never forgot the cost of a loaf of bread, and I never forgot the cost of launching a training program. And that, and wanting to just be deeply relevant to the business and to the culture. The L and D team at Facebook was revered, and I still, I just posted yesterday on LinkedIn, I posted a photo of the group of people that I onboarded with the team at Lacework this week.

And my favorite part was all of the people underneath it from my Facebook days who were like, I remember when you did my onboarding at Facebook, and it completely set the tone, and it was like, I've, I'll never forget it some of those people I onboarded 10, 11, 12 years ago. And that is what I want for every L and D team.

And you cannot do that if you are not deeply tied to what matters. Not only to the business but the people in it. Because every one of those managers, every one of those new employees, whether they knew it at the time or they realized it after, appreciated the fact that wow, these guys really set me up for success here.

They really played a pivotal role in helping me be successful here. Yeah. Yeah. It just never, like the whole time I was in consulting, I never once marketed, it was all directly people that either I worked with at Facebook. They were like, "Hey, can you come help us do something like that here?"

And then people that I met at clients who then went on to other companies that did the same thing. I think for anybody who works in learning and development, that should be the goal. Like how can I be so deeply meaningful, not just to my executives, but to the students, the learners that they see us as indispensable?

Tom Griffiths

Such a beautiful through line starting with onboarding and then through the the journey of the learner at Facebook. I think it just, again, is another manifestation of the value that Facebook placed on learning and development such that it's integrated into the onboarding process so that you've already got a relationship with everybody coming into the company and they have that reverence for you as a department and a warmth towards future programs that you might provide.

Rather than appearing as the training folks trying to, nudge people to do stuff when they've got a million other things to do. That's a great way that it unfolded there. So we talked a little bit about budget as a stumbling block potentially, but if we say we've got the budget, what other stumbling blocks have you seen people run into when it comes to rolling out a learning program or trying to build a learning culture?

Mike Rognlien

I think I think I talked about this in the book. The bias program was a really good example. We wanted desperately to buy something off the shelf 'cause again, like we, in order to move quickly and to be able to manage all of these other priorities, one of the things that enabled us to do that and to scale really important programs quickly was being able to partner with vendors and content providers.

There wasn't a program or a product out in the marketplace at that time. I honestly don't know that there is one today, even though it's a much bigger, more popular topic today than it was nine years ago, eight years ago. We desperately wanted to buy something off the shelf, and we couldn't find something that met the need.

It became a program that I got brought in to help develop, and I remember when I got the call, and I went to meet with Sheryl to start working on, I'm like, Sheryl, I don't know anything. I'm passionate about DEI, and I'm passionate about it as a topic, but I don't have any subject matter expertise or research on this. She had just written Lean In a year or two before, and she had worked with a ton of researchers from Hastings, UC Berkeley, and Stanford, like Cheryl's Rolodex. She's we're gonna be fine. I'll call some people.

But it became looking at the marketplace and saying there isn't actually a product out there. And this is a decision that we're gonna make to actually build it ourselves. And I am so grateful A, that we did, and B, that she had the willingness to say, we are actually gonna be the ones to define this.

And then, in true Facebook fashion, after we built that program and kind of got our legs under us teaching it, Sheryl and I taught the very first session to Mark and his executives. That was the very first session that we did. They were a pilot group, Guinea pigs. They were our pilot group, and because it was one of those things where it's yes, culture is everybody's responsibility, and if our leaders don't walk the talk here, nobody else will either.

And so it was me, Sheryl, and Mark, and all of the senior leaders in the company, the head of every department, including Jay, who's now my boss at Lacework the CEO at Lacework. And we did the session as design. And Sheryl was like, look, if you guys aren't gonna get behind this and be willing to talk about your own biases, admit that you're human beings, blah, blah, blah, this isn't gonna work.

We could have never done that with an external vendor. It just wouldn't have worked. Not, and then, like I said,, in true Facebook fashion, in addition to rolling the program out internally, we filmed, we had a professional version of it filmed. It was me, Maxine Williams, who was the head. It's still the head of DEI at Facebook, and I think Lori opened it, the Head of the People team, and we filmed it and we put it on the internet, and it's still there.

We released it probably eight-nine years ago, and it's still there, and companies still use it. So I think the other thing that made us valued and valuable as a learning function was that we recognized when we really did need to do something ourselves. And because we would've stolen with, not stolen with pride, but we would've easily said, Hey, Google, you built a really great program.

Can we partner with you on this? Or, Hey, Apple or Microsoft. There just wasn't anything there. So we decided to be the change that we were seeking, built it ourselves, and open-sourced it so that anybody could use it to drive similar conversation.

Doing stuff like that, recognizing when there's a hole in the market that we can help fill, and we have the resources, we have the money, and we have the ability to do it then we should, and I would love to see more L and D teams not to share the impact of what work they did, but share some of the work as well.

'cause ultimately, it's not a zero-sum game, I think we really felt that if the world of business gets better at talking about bias, the world gets better. And that benefits us in two ways, not only the work that we're doing internally but the value of the work that's being done externally.

So there's lots of stuff like that I think that companies can do to continue innovating and continue to evolve the profession of learning and development. Yeah. Yeah, it's a beautiful thought and being part of something bigger. Again, perhaps living that openness value of sharing with the world the work that you've done.

Tom Griffiths

It's wonderful, and it's a nice note to wrap up here. I've just got two rapid-fire questions, Mike. First one's, stop, start, continue. Given current trends in the industry, what do you think the average learner leader, or learning leader should stop doing?

Mike Rognlien

What do I think they should stop? If you're not already a lean learning machine, I think you should stop doing programs at the company, at the company L and D levels. If you are an enterprise-level L and D team, you should stop doing things that don't lie that aren't a rising tide that lifts everybody in the company's boat.

Like ruthless prioritization, and by the way, ruthless prioritization should be painful. If you're not feeling any pain, you're just rank order. You're not prioritizing. So, really decide what are the things that make or break our culture here and double down on those. So stop doing anything that doesn't meet that criteria.

Tom Griffiths

That's great. What about start? What should people start doing that they're not already?

Mike Rognlien

Similar to what I said earlier, if you aren't already using a systemic view and approach to how you're making decisions with your business leaders about what content you should be owning and developing and driving or buying off the shelf, again, what are the expectations? What are the learning mechanisms that can help people meet those expectations? And then what's the accountability? If you're not involved in the conversations about expectations and accountability, you really should start the proverbial seat at the table. I don't care if you have to bring your own chair and your own side table; get in that thing so that when those conversations about expectations and accountability are happening, you're a key partner to them.

Tom Griffiths

Absolutely. So start crashing the executive team meeting. Love it. And to give folks credit for things they're already doing, they should just keep on at. What should people continue doing?

Mike Rognlien

I think continue to be the inspiration for curiosity in your organizations. I one of the things that I think made me successful, that I certainly coached everybody on my team to do as well, was to be just as humble about what they were learning.

The bias program that we just talked about was a great example. One of the reasons that I was concerned about not being behind the scenes, designing the content was a big enough challenge. I was really concerned about being up in front of the room. 'cause my rule has always been if I can't talk about my own experience, how I relate to the content and.

Really importantly, how I've screwed it up then and learned from it, I can't get up there and do it. Fortunately, there were lots of examples in the research that I could relate to to say, oh yeah, I've made that mistake. That type of role modeling that I have mixed feelings about the term vulnerability, but being able to get up in front of a room and say, this is a really important skill set.

I've struggled with it. Here's some examples and here's what I've learned from it, and I believe that you can too. That is the number one thing that I think people really valued me and my team for was that willingness to go first and I wrote in the book about being a scientist of your own behavior.

Being willing to not only be a scientist of your own behavior but a scientist that publishes their results talks about them with other people and says, Hey, this crucial conversation stuff is hard. Let me talk about what I've learned through trial and error and the mistakes that I've made over the years, and hopefully, an effort to push the fast-forward button on other people's development, which is really what we're there to do.

So for those people that are already doing that, continue doing it, do more of it. Be confident that one of the things that people really value about learning and development people is our willingness to publish the results of our own self-studies. I love that. It's a great way to frame it, and scientists who publish the mistakes and the learnings as well just make it so much more authentic and resonant for people.

Tom Griffiths

That's wonderful. Last question. If you were speaking to some of the aspiring learning leaders who listen to the podcast, what's one tip that you would give them to stand out to their team and their executive team as they grow themselves and their careers?

Mike Rognlien

What is the organization's unique culture, and what unique experience do I bring to help bring that culture to life? It's one of the things that prevents people from having a seat at the table and gives them imposter syndrome and all those other really unhealthy things that, unfortunately, I think a lot of learning leaders and HR people spend so much time trying to like, speak the language of the business.

By learning all of the financial terms and being able to talk in detail about the product, things that really aren't, and why we're there, you are going to have the greatest impact by being the best version of a learning person. And I don't remember the last time any executive from any department was like, let me really learn how to speak the language of l and d because they shouldn't.

And I shouldn't necessarily have to become fluent in the language of finance. That doesn't mean that I'm not in tune with what those people need, but we have to have the confidence that we are there for a reason, that the stuff that we bring to the table is just as valuable in some cases, if not more so than some of the other things that the rest of the business brings.

And to just really have the confidence that. You are there because you meet a business need, just as accounts payable meets a business need. Just as an engineer, shipping a product, meeting a business need, and really doubling down on that, the best way that you're gonna succeed as a learning and development leader is being really good at learning and development, not by.

Being able to do the quarterly earnings release for the schedule.

Tom Griffiths

That is such great advice, Mike. Thank you for such a deep and inspiring conversation. We could, I think, talk for hours more about so much of your experience. It's riveting and honestly, the anecdotes from Facebook and elsewhere really bring it to life for people and show what an example learning culture can be if there's buy-in from the top and excellent learning leaders like your folk, like yourself driving it. So, thanks for spending time with us. Thanks for a great conversation, and looking forward to seeing what you do in the future.

Mike Rognlien

Thank you. Thanks for having me.

Amazing. Honestly.

Episode transcript

Tom Griffiths

Alright, we're back with Mike Ronglien. I'm super excited to continue our conversation. In part one, we went deep into the culture and his time at Facebook and how that evolved. In part two we're gonna talk about the role of l and d in shaping that culture and helping the company succeed. Mike, you were head of L and D at Facebook for over seven years.

What role do you see for L and D in building or maintaining that company culture?

Mike Rognlien

Yeah, so I think first and foremost is what we were talking about in the first segment, the difference between being a training department and a learning and development department. Stu, who we're talking about on break, is the guy that hired me on Facebook.

That was one of the things I think that philosophically, we were very aligned on was that I had no desire to come in and just build a training repository of a hundred different classes. I really wanted to, and they gave me as much as you could take a lot of time. They gave me some time in the beginning to really get a sense of.

What is the special sauce that makes this company work? And what are the skills that are behind those things? So we talked about being open and moving fast, no matter how much you can nod your head and say, yeah, that sounds awesome. Living up to it is a whole nother ballgame.

So I think the most important thing that any L and D team can do is to really say, what are those critical skills that we absolutely will not have in this culture? We will not be able to live up to these values unless we teach people them. And just relentlessly, Cheryl called it ruthless prioritization but really making painful decisions to say, I would love to be able to do five things next year, but we're gonna choose these three because they're the most culturally relevant.

And it's funny 'cause this has been such a walk down memory lane 12 years ago when I started; I remember one of the first meetings that we had as an L and D team after I started was to really decide what are we gonna focus on? What are we gonna prioritize? And one of the things that people had been asking about was some kind of interpersonal communication skills type program. We were very engineering-heavy heavy, very young. All of our managers, including, I think, Mark was 26 or 27 when I started. So there was a lot of really incredible talent, but from a soft skills perspective, it wasn't necessarily as advanced. We said we would really love to do some kind of interpersonal skills training, but it's just not as important as onboarding and a co and some other manager development stuff.

So we deprioritized it and then, I don't know, it was May, I think it was maybe the end of my first or second month with the company, and Cheryl did an internal talk for managers and leaders. And she did her, here are my thoughts on managing and leading and what I'd like to see you all do here at Facebook.

And at the end, somebody got up and asked, "What's your biggest concern about the company as we're about to, do this, go through this vertical growth ramp, not just in terms of the product, but in terms of the people?" And she didn't miss a beat. We're gonna stop being open and honest with each other.

People are gonna know each other less, so they're gonna be less direct and all of the kind of negative side effects that come with less direct communication are gonna befall us. And Lori, who ran the people team, was sitting on one side of me and Stu, my boss was sitting on the other side and we had just recently decided we weren't gonna do any type of interpersonal communication training.

And I just looked at both of 'em like, are we really not gonna do this? Like she's both, she's all three of our boss. Are we really not gonna do the thing that, addresses her biggest concern and they were like, Nope, let's go back to the drawing board. And in the spirit of moving fast and being bold and all of those value-based decisions, we reprioritized and added in a class called Crucial Conversations which I had taught at Microsoft and was a big advocate for.

And six weeks later we launched that program globally. And. I don't know if they still, I believe they still offer it, but in my time it became not only the most popular program in the company but also the most culturally reinforcing. It just, came up all the time and became a lot of the skills underneath that program, having them be present and having them be so prioritized and talked about and discussed in the culture.

Made it, I think, a lot easier for us to launch the unconscious bias training that we ended up building a few years later. And that's, I think, by the way, why Cheryl wanted me to help her build it was because I had operationalized that crucial conversation implementation really quickly. And it was, they became two topics that we really bonded over.

Tom Griffiths

Wow, there's so much in that and what you just said. First and foremost, wanna give Stu a shout out. As you mentioned him there, he was an advisor at Hone in our early days, and helped us build a lot of early content, so thank you Stu. And yeah, just sounds like you, as a learning team, lean and mean really embracing that move-fast culture in how you were.

Supporting the organization and talking a lot to learning leaders and people, leaders about how you can get a seat at the table or work more strategically with business leaders, and listening deeply to concerns that Cheryl had. And then building learning programs directly to address those. Seems, you know exactly the right kind of way to build that relationship and support the strategy more effectively. So that's great. It sounded like you three four or others built a lot internally or adapted stuff internally. And just curious how you brought the values into the content. 'cause I know you wanted to tackle the subjects head-on but did you bring in the kind of mantras we were talking about earlier, how did you actually make it feel like Facebook when you built the training?

Mike Rognlien

I love that you asked that question. 'cause professionally and from a personal perspective, speaking professionally, I think my proudest contribution, not just to learning and development at Facebook, but really to the profession was. the ways that I went about and that we went about building customized versions of content with these vendors.

There were two things that I wanted to achieve at the same time. Number one, I didn't want to build a bunch of stuff from scratch. Crucial was one of the programs. We also did situational leadership from the Ken Blanchard companies. We used a lot of Marcus's content on strengths and strengths-based leadership from T N B C.

I had no desire to reinvent any of their work. They were the best in the world. But at the same time, I also knew from teaching Crucial for years at Microsoft that I was constantly at the beginning. It became a funny thing, but also a necessary evil. I would ask at the beginning of every session of Crucial, raise your hand if you've ever seen a really great, compelling, realistic training video.

And of course, nobody would ever raise their hands. Good. You're not gonna see any today either, and it's a lighthearted way to acknowledge the fact that the video content was really not realistic. And at Microsoft that, got the laugh and made the point and then I showed the videos anyway.

By the time I got to Facebook, I was like, these guys are just gonna eviscerate it. Yeah. They're gonna look at a bunch of mostly white, middle-aged dudes in mahogany conference rooms talking down from the 1990s talking down to younger female employees and just be like, are you kidding me with this?

I went to VitalSmarts and was like, I love, which is now crucial learning. I went to them and said, I love you guys. I love your content. It is life-changing and the way that it is presented is absolutely going to render it ineffective here. So you're gonna have to either be willing to let me and my team customize it and trust that we are enamored enough with and in love with your content and the research behind it to do it justice, or we're gonna have to figure out something else. And to their credit, they were like, all right, we've never done a deal like that before. We've always just said, okay, here's the number of workbooks, and if you need trainers, here's how much that costs.

And then, go implement. And we did, we completely customized it and we ended up doing the same thing with situational leadership too. And with Marcus's content, I think my biggest superpower was always being able to see how all of that stuff worked together. So our management training, which became, it wasn't just manager training, it was management training.

It was open to everybody became if every manager and leader and person in the company understands the importance of strengths and how to identify them, if they understand the way that you need to shift your approach, Allah situational leadership, as people are growing and changing, and if you're comfortable having those difficult conversations about things that pop up along the way, we really feel like you're gonna be 90% of the way there.

And so that kind of became how we built those early. Those early programs and then later programs all followed the same thing. But I built nothing from scratch. I sorted the content that I thought was the best that other people agreed was the best. And then we customized it and now, there are tons of different ways that a class like Crucial, you can customize, you can reorder slides, you can add stuff in.

You can take it out. You can do a one-day version, you can do a two-day version. There are people wearing jeans and the building isn't on fire. There are so many different things that I know because they've given us feedback that we really had a positive influence on. And I'm proud of that.

The industry was very locked down and very do it our way. We're the experts and I think it's a much more open flexible, way of getting learning out to people now. If your end goal is optimizing towards relevance and applicability at an organization you've gotta be able to tailor it to what.

Tom Griffiths

The learning leaders know what their audience is looking for and as you say, starting from scratch is also inefficient and not necessarily gonna produce the right results. So, finding that vendor partnership that you can tailor in the right way is the sweet spot.

You had a big bootcamp program at Facebook, would you have those training programs as part of that, or was it, come whenever you're ready or at certain inflection points in a career journey, how did you actually roll that out or invite people to take part?

Mike Rognlien

D, all of the above. So again, picking programs and the skills that those programs brought that were deeply cultural, culturally relevant. Because they were so culturally relevant, there were a million different ways to implement them. So bootcamp is a great example. Bootcamp was, for the unfamiliar, basically the way that we brought engineers into the company.

For years, I don't think they do this anymore, but for years the way that we hired engineers was we just hired engineering talent and then they would spend their first six to eight weeks at the company or so in bootcamp. They would just be solving problems and learning about different parts of the site, as the company and the product got bigger, there was more to experiment with, and then they would pick the part of the product that they wanted to work on.

So some people were like, I wanna work on facebook.com. Some people were like, I want to build for mobile. Some people were like, oh, Instagram's brand new. I wanna go play over there. And then there were people that were like, I wanna be behind the scenes. I wanna figure out how to make all of the servers that have to work together around the world to serve these apps on a billion, 2 billion, or 3 billion phones that's my jam. So that's where the interns that would take the site down would go, is that right?

I remember there was a like handmade banner that a woman named Melissa Han, one of the early recruiters, and her brother Bob was one of the early engineers. And I remember walking in, I think it was for my interview, and there was like a handmade, like a homecoming football game type poster.

And that said, this site is, and then there was like a space to either put up or down. And then after, it was like, good job. Anyway, so bootcamp was a way to let people experiment. So if you're gonna do that successfully, then the bootcamp mentor the people that were already there that were mentoring these new engineers, they had to be able to use the principles of like situational leadership in order to really help.

These people that are, they have six weeks to figure out basically what they want the first part of their career at Facebook to be. And so those bootcamp mentors ended up saying, that situational leadership thing that you're doing for, mainly for managers. I'm not a manager, but I am mentoring people, so I need to help.

People move through that development curve. So I need to take situational leadership. So we put that in the bootcamp training we had a number of people who were customer-facing that were like, we're pretty good internally with how we communicate, and we don't really have a lot of unhealth.

We have conflict, but it's not unhealthy. But God, some of our customers, holy crap. So it's great. Then let's come in and do a session on crucial conversations that is specifically focused on having crucial conversations with advertisers. So every skill that we picked for years, there were like five, and they were all deeply culturally relevant because they just permeated everything that we did and how we got our work done.

And that really didn't change the whole time I was there. We were doing the same kind of core courses. We added classes like bias and stuff along the way. But for the most part, we were doing the same exact programming when I left at 26,000 people that we had started with in my first six months.

Tom Griffiths

Yeah, that's such a testament to how you all set it up and fascinating that you would adapt it, like you said, for conversations with advertisers as a special case to really apply the material to that and teach people how to do it. So specifically that, that's really cool. This term learning culture bringing together, our two threads gets bounded around a lot.

I'd just be curious if you find that a useful term and how you define a learning culture and it would be great to talk about how do you build a learning culture and know that you have one?

Mike Rognlien

Yeah. Again, timely because this is a question a variation on a question that we're asking internally at Lacework.

How do we know if we have a high-performing culture? First and foremost, if you're on high high-performing culture, you have to set high goals, right? You have to have really high standards for what you're going to accomplish. 'cause if you don't have that, you can't really be a high-performing culture 'cause you're not working on stuff.

That's hard enough. I think for a learning culture. I think it's a wonderful term and it's a wonderful environment to work in, but there's a precursor to that, which is that you have to prioritize and value curiosity. You can't hire a bunch of people who are like, I already know everything I need to know, or, I've got 20 years of experience, you're not gonna teach me anything.

'cause you can't have a learning culture without learners. And learners tend to be curious. It's actually one of the things I think I got introduced to you all. Via a podcast that I had posted on LinkedIn that Jay, our CEO had done. And I was going back and forth with one of your colleagues that I used to work with at Facebook and about this podcast.

And that podcast that I had posted about was Jay talking about all of the lessons that he's learned along the way as a leader. And one of them was that he just deeply values curiosity. And he also demonstrated that Mark was the most curious executive I've ever worked with in my life, just insatiably curious about everything.

One year, he did a book club for a year where anybody in the company could, if they wanted to read the book that Mark was reading, and every other week or so, he would host a book club in his conference room which was when Facebook was probably 15 plus thousand people. So we weren't just a tiny little company.

Like it was a thing, and people would, I guess, it wasn't Zoom at the time, but they would video conference in from all over the place, and we would sit in a circle have a discussion about what, and it wasn't like, we're gonna read Oprah's book Club, nothing against Oprah's Book Club as I'm looking at Oprah's book, club book that's sitting right there.

But the one that I, the one that I went to, 'cause I was, swimming way upstream from my standard skillset was like on the ethics of mapping the human genome. It was one of the days that I think I felt the best about working at Facebook because you've got all of these people from different functions, mostly technical folks, but people from all around the company, a bunch of people on video conferencing was sitting in Mark's conference room, and his ability to synthesize and then have questions about the content in that book, which was way over my head.

I just thought what an incredible organization to work in, where the CEO of the company is taking an hour and a half out of his day on top of the time that he took to actually read and understand the book to talk and wax philosophical and poetic about the ethics of mapping the human genome with a bunch of his employees.

You can't have a learning culture without curiosity, and you really, it's, you're really hard-pressed to have a learning culture without curious leaders. I know I talk a lot about shared ownership and how everybody has skin in the game, but leaders do disproportionately influence that. And if you don't have curious leaders and if you don't have leaders who, as I said at the beginning of our conversation, leaders like Jay, who it's just baked in that they value learning.

It's really hard to do that. So I tell people that are in this profession when they're interviewing for companies, ask them, what was the last book you read? Or what was the last concept that really changed how you viewed a significant part of running your business?

Because it's gonna be pushing a boulder up a mountain to try and get them to value that type of curiosity and that dedication to continuous learning.

Tom Griffiths

It encapsulates so much that concept of curiosity and the story of Mark doing the book club for 90 minutes every couple of weeks, and making time for that is so iconic, right?

Because we hear sometimes from people, I haven't got time to do learning. I've got too much to do. We're talking about Mark Zuckerberg running Facebook and all the other acquisitions. finding an hour and a half every two weeks to just do not even work relevant learning necessarily. But just following his curiosity, and that's just such, setting such a great example for the team at Facebook, but also, I think more broadly how leaders need to make the time to prioritize learning because it models it for everybody else. And if you can do that, then it'll cascade and build that learning culture. It's an awesome anecdote. Thanks for sharing it. Are there other things that you, as a learning leader, can do? Say there's buy-in from the executive team, or maybe you need to get a little bit of buy-in from the executive team, but how do you actually operationalize a learning culture?

Mike Rognlien

Yeah, that's a really good question. So when I came into Lacework the first few meetings that I had with senior folks were really educating them about how I get my work done.

I think if you want a learning culture, again, you have to have curiosity, but you also have to understand that, especially if you're coming from nothing, which Lacework really doesn't at this point have management and leadership training. They were doing some coaching with an external vendor, and they had some programs in place, but nothing programmatic that was like, this is how we think about manager development, for example.

And it's probably a combination of, I was very fortunate at Facebook. I really didn't have to justify anything monetarily, budget-wise, philosophically, as I established early on that I'm here to focus on the most important stuff and, with people like Stu and Cheryl and Mark behind it.

It was pretty easy to just get that stuff done now, and it's a function of spending six years in consulting between my last full-time job and my current one. I am much more I spend a lot more time educating people about the process, about how this stuff has to work. So, I tend to talk about learning and development as a systemic solution.

That is dependent upon two other things in order to really work. The first is, and I'll use manager development a, and as an example. We didn't have clearly defined, communicated expectations for managers, which is not surprising. A lot of smaller companies don't even, and some larger companies don't.

And in the past, I would've been tempted to say that it doesn't matter. We're just gonna plow forward and do some training. What I know from a, from an experiential perspective, the managers that are actually being asked to take the training, Justifiably, you're like, I don't know why I would do that.

Like, why would I go to training when I have no idea how it relates to anything that's related to my job? So the first prong, I think that if you want to have that learning culture, you have to get very anchored into what are the expectations that any learning or development opportunity. Would it actually tie to why would somebody want to develop this skill?

As I said, with crucial conversations at Facebook, it was clear be open is valuable. Being able to communicate effectively and be able to handle conflict and all of that was something that you would be held to account to. So because that expectation existed culturally and professionally, It was something that people did.

The same thing applies here. So, the very first thing that I did as an L and D professional was not to roll out training, it was to roll out manager expectations. So that there's a foundation upon which to build. The second piece, which is what people in L and D are most typically known for, is the actual learning experience, which I'm working on now.

And I can't, the, a lot of these folks have not had this type of training before. They've never had it at Lacework, so I can't just go guns blazing and throw 10 different programs at them. I went around and talked to managers, leaders, individual contributors all over the company. It was like, what do you think is the most important skill for us, all of us, to get better at first?

And it was being able to give and receive feedback. Great, we'll start there. And then the third piece of it that, that, and all of this happens to some degree concurrently. The third piece is, are we gonna hold people accountable? 'cause without accountability, the expectations aren't taken, be taken seriously, and then neither will the training be.

So the third piece is how are we gonna hold people accountable? And are we going to specifically hold people accountable for their ability to meet the expectation of being good at delivering and receiving feedback? So I won't even sit down to talk about a training program until I know that we're gonna sit down and talk about all three of those things.

That in and of itself is a learning process. 'cause a lot of times, again, if you're coming from a more traditional, maybe older school training department, it's the executive asks for something, and you say, what time? Versus saying, hold on, what is the expectation? How are we gonna hold people accountable?

And when I say hold people accountable, I mean reward them for doing it really well and have there be some kind of a meaningful consequence for not doing it really well until we have that whole system mapped out. I'm not really ready to launch into a training program. I don't think that any of us are doing any of our internal or external clients a service.

If we don't, again, from a curiosity perspective, say, great that you wanna do this type of training, what expectation is it gonna map to, and what accountability measures are gonna be in place to make sure that the people that do this training are actually living up to the expectation that we've set.

Tom Griffiths

It is so powerful to link it to almost the business problem that you're trying to solve. So everybody sees that it's important, not just training for its own sake. Like you say, on the whim of an executive that may be here today, gone tomorrow. And that allows you to. Not only motivates the learners but also justifies the program in the first place and ultimately measures the success at the end.

We have a lot of conversations with our clients and folks in the industry around this question of how do I justify learning budget, especially these days when times are a little tighter. So I'd just be curious if you had any advice for people who are going through that process of trying to justify a learning program to the executive team.

Mike Rognlien

I think being, first and foremost, being willing to be as nimble as the rest of the company, right? Like when times are tight, everything gets tighter, travel. Discretionary travel gets tighter. Team development offsite stuff like that tends to get tighter. So I think first and foremost, that's one of the reasons this was all born out of necessity.

Slower times at previous companies, when I knew that things were gonna get cut, it's why don't we just not have a bunch of fat in our budget in the first place? Why don't we not? Do a bunch of training programs that aren't really needed, that aren't the most important in the first place.

Because if I can't believe I'm gonna quote RuPaul's Drag Race, but one of the things I love, RuPaul says, right? One of the things, again, is the learning culture; you can find tidbits everywhere. I love RuPaul for a number of reasons, but I. She's H"ey, if you stay ready, you don't gotta get ready."

And I think the same thing applies here, right? If, if you have the right focus, the right content, and the right prioritization, and that program, those critical few important programs that you do are deeply tied to expectations that are deeply tied to accountability. I think by taking that systemic view of learning, I think you're predisposed to being ready for it.

Spoon times and leaner times, but I've never looked at, 'cause again I, the one thing that I will tell people that was just earth-shatteringly different about Facebook was I literally had no budget. And when I say no budget, no budget limit. Like whatever we needed must be nice. It was, and I wasn't stupid about it.

I'm like, yeah, I don't need that money. Yeah. Or I know that we could do that program, but it's just gonna be a distraction. It's gonna take, again, it'll be motion but not progress. There was a lot of stuff that we didn't do, even though we would've never had to ask twice for the money for it, because it just wasn't the most important thing to do.

I was never asked to really anything in or or cut anything while I was at Facebook. I know that they have every department that the company has. But I think starting my tech career at Intel when I. They were coming off of five, I think, three stock splits in five years.

The money was flying everywhere. Everybody was spending tons of money on everything, and then the floor fell out, and the whole time I was there, it was just shrinking and cutting and shrinking and cutting, and it was painful. But it's, it's like grandparents that grew up during the depression.

They never forgot the cost of a loaf of bread, and I never forgot the cost of launching a training program. And that, and wanting to just be deeply relevant to the business and to the culture. The L and D team at Facebook was revered, and I still, I just posted yesterday on LinkedIn, I posted a photo of the group of people that I onboarded with the team at Lacework this week.

And my favorite part was all of the people underneath it from my Facebook days who were like, I remember when you did my onboarding at Facebook, and it completely set the tone, and it was like, I've, I'll never forget it some of those people I onboarded 10, 11, 12 years ago. And that is what I want for every L and D team.

And you cannot do that if you are not deeply tied to what matters. Not only to the business but the people in it. Because every one of those managers, every one of those new employees, whether they knew it at the time or they realized it after, appreciated the fact that wow, these guys really set me up for success here.

They really played a pivotal role in helping me be successful here. Yeah. Yeah. It just never, like the whole time I was in consulting, I never once marketed, it was all directly people that either I worked with at Facebook. They were like, "Hey, can you come help us do something like that here?"

And then people that I met at clients who then went on to other companies that did the same thing. I think for anybody who works in learning and development, that should be the goal. Like how can I be so deeply meaningful, not just to my executives, but to the students, the learners that they see us as indispensable?

Tom Griffiths

Such a beautiful through line starting with onboarding and then through the the journey of the learner at Facebook. I think it just, again, is another manifestation of the value that Facebook placed on learning and development such that it's integrated into the onboarding process so that you've already got a relationship with everybody coming into the company and they have that reverence for you as a department and a warmth towards future programs that you might provide.

Rather than appearing as the training folks trying to, nudge people to do stuff when they've got a million other things to do. That's a great way that it unfolded there. So we talked a little bit about budget as a stumbling block potentially, but if we say we've got the budget, what other stumbling blocks have you seen people run into when it comes to rolling out a learning program or trying to build a learning culture?

Mike Rognlien

I think I think I talked about this in the book. The bias program was a really good example. We wanted desperately to buy something off the shelf 'cause again, like we, in order to move quickly and to be able to manage all of these other priorities, one of the things that enabled us to do that and to scale really important programs quickly was being able to partner with vendors and content providers.

There wasn't a program or a product out in the marketplace at that time. I honestly don't know that there is one today, even though it's a much bigger, more popular topic today than it was nine years ago, eight years ago. We desperately wanted to buy something off the shelf, and we couldn't find something that met the need.

It became a program that I got brought in to help develop, and I remember when I got the call, and I went to meet with Sheryl to start working on, I'm like, Sheryl, I don't know anything. I'm passionate about DEI, and I'm passionate about it as a topic, but I don't have any subject matter expertise or research on this. She had just written Lean In a year or two before, and she had worked with a ton of researchers from Hastings, UC Berkeley, and Stanford, like Cheryl's Rolodex. She's we're gonna be fine. I'll call some people.

But it became looking at the marketplace and saying there isn't actually a product out there. And this is a decision that we're gonna make to actually build it ourselves. And I am so grateful A, that we did, and B, that she had the willingness to say, we are actually gonna be the ones to define this.

And then, in true Facebook fashion, after we built that program and kind of got our legs under us teaching it, Sheryl and I taught the very first session to Mark and his executives. That was the very first session that we did. They were a pilot group, Guinea pigs. They were our pilot group, and because it was one of those things where it's yes, culture is everybody's responsibility, and if our leaders don't walk the talk here, nobody else will either.

And so it was me, Sheryl, and Mark, and all of the senior leaders in the company, the head of every department, including Jay, who's now my boss at Lacework the CEO at Lacework. And we did the session as design. And Sheryl was like, look, if you guys aren't gonna get behind this and be willing to talk about your own biases, admit that you're human beings, blah, blah, blah, this isn't gonna work.